DEBORAH AYERST artists’ agent (415) 567-3570 ︎ ︎ ︎ ︎ ︎

animation design experiential fabrication illustration motion music photography

art & performance

SIDESHOW

The sideshow archive is a personal project of mine that I created in 2000 in the brick and mortar space and morphed it here in to the digital space. The concept behind sideshow is that I have met and continue to meet many individuals at their day jobs in our business of advertising and design, only to discover in getting to know them, they have amazing creative interests they pursue on the side that are well worth bringing to light. Whether the receptionist at a clothing company or an Executive CD at an ad agency, the mandate of sideshow is to give that receptionist or that ECD a place to showcase their art, no matter what form it takes.

Long ago, I started out on the fine art side before I became an agent for advertising, working at a gallery in Los Angeles that brilliantly ran shows of contemporary painting, art films, video art, poetry readings (how I got to meet Bukowski!), conceptual, performance work and beyond. It was a stimulating and freely open format and the curator I worked under was a true Beat spirit from New York. Andy Warhol will always be one of my heroes & I believe that my own interest in curating the important, the funny, the pop, the beautiful or the disruptive is well served by sideshow.

JASON WARNE & NOAH DASHO

day job: Effects Technical Director / Pixar

sideshow: Visual Artist / Painting

![]()

artist statement: ART NIGHT

April 11, 2013:

I know we are both ridiculously busy and you decided to buy a house as far away from mine as possible but seriously, we need to do an art project to keep our sanity (or is it integrity?). Wouldn’t it be weird to see our styles combine? We should pass some drawings back & forth. Make each other laugh, draw some random shit, see where it goes. Might suck. Might be rad. I NEED TO ACTUALLY MAKE SOMETHING! What say you?

FUCK YEAH!

April 12, 2013:

It’s on! I grabbed some boards that will be easy to pass back & forth. I CAN’T WAIT TO DRAW, PAINT & COLLAGE THE CRAP OUT OF THESE!

GAME ON.

Rules?

No rules. Free reign. Anything goes. Start one, start another one, keep ‘em flowing.

Irish Bank? A beer & we’ll make it our weekly exchange place?

Can’t, I’m slammed. …Fuck it. Let’s go!

August 8, 2013:

I hooked up a venue to show our boards, something called Sideshow! I am thinking we try to go all legit with the statement. Something like “Art Night’s contrasting styles, humorous subject matter & at times seemingly random imagery invite audiences to initiate a dialogue between reality and imagination. The collision of Dasho’s naturalistic birds with Warne’s nostalgic & iconic illustrations creates a shared communication with both natural & pop-cultural references”.

NO. ABSOLUTELY NOT.

The sideshow archive is a personal project of mine that I created in 2000 in the brick and mortar space and morphed it here in to the digital space. The concept behind sideshow is that I have met and continue to meet many individuals at their day jobs in our business of advertising and design, only to discover in getting to know them, they have amazing creative interests they pursue on the side that are well worth bringing to light. Whether the receptionist at a clothing company or an Executive CD at an ad agency, the mandate of sideshow is to give that receptionist or that ECD a place to showcase their art, no matter what form it takes.

Long ago, I started out on the fine art side before I became an agent for advertising, working at a gallery in Los Angeles that brilliantly ran shows of contemporary painting, art films, video art, poetry readings (how I got to meet Bukowski!), conceptual, performance work and beyond. It was a stimulating and freely open format and the curator I worked under was a true Beat spirit from New York. Andy Warhol will always be one of my heroes & I believe that my own interest in curating the important, the funny, the pop, the beautiful or the disruptive is well served by sideshow.

JASON WARNE & NOAH DASHO

day job: Effects Technical Director / Pixar

sideshow: Visual Artist / Painting

artist statement: ART NIGHT

April 11, 2013:

I know we are both ridiculously busy and you decided to buy a house as far away from mine as possible but seriously, we need to do an art project to keep our sanity (or is it integrity?). Wouldn’t it be weird to see our styles combine? We should pass some drawings back & forth. Make each other laugh, draw some random shit, see where it goes. Might suck. Might be rad. I NEED TO ACTUALLY MAKE SOMETHING! What say you?

FUCK YEAH!

April 12, 2013:

It’s on! I grabbed some boards that will be easy to pass back & forth. I CAN’T WAIT TO DRAW, PAINT & COLLAGE THE CRAP OUT OF THESE!

GAME ON.

Rules?

No rules. Free reign. Anything goes. Start one, start another one, keep ‘em flowing.

Irish Bank? A beer & we’ll make it our weekly exchange place?

Can’t, I’m slammed. …Fuck it. Let’s go!

August 8, 2013:

I hooked up a venue to show our boards, something called Sideshow! I am thinking we try to go all legit with the statement. Something like “Art Night’s contrasting styles, humorous subject matter & at times seemingly random imagery invite audiences to initiate a dialogue between reality and imagination. The collision of Dasho’s naturalistic birds with Warne’s nostalgic & iconic illustrations creates a shared communication with both natural & pop-cultural references”.

NO. ABSOLUTELY NOT.

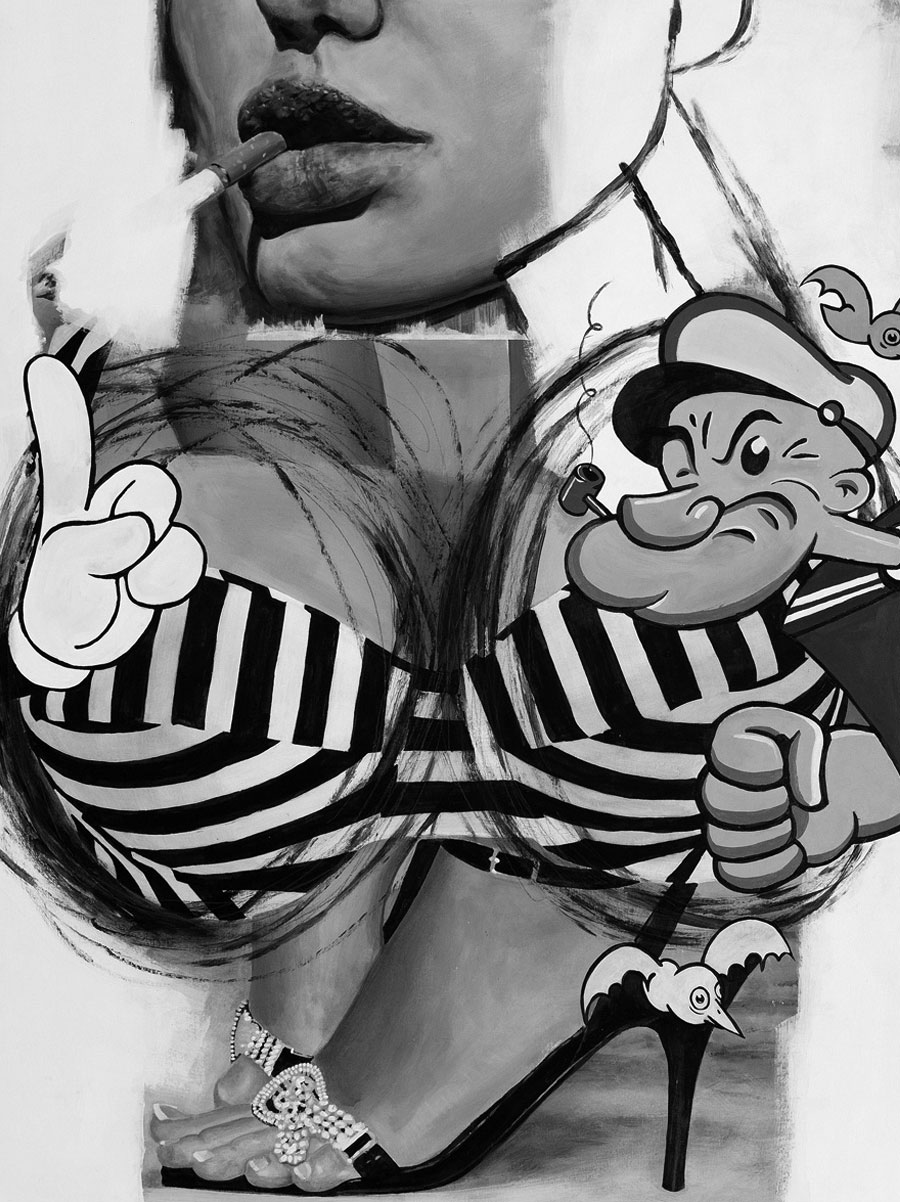

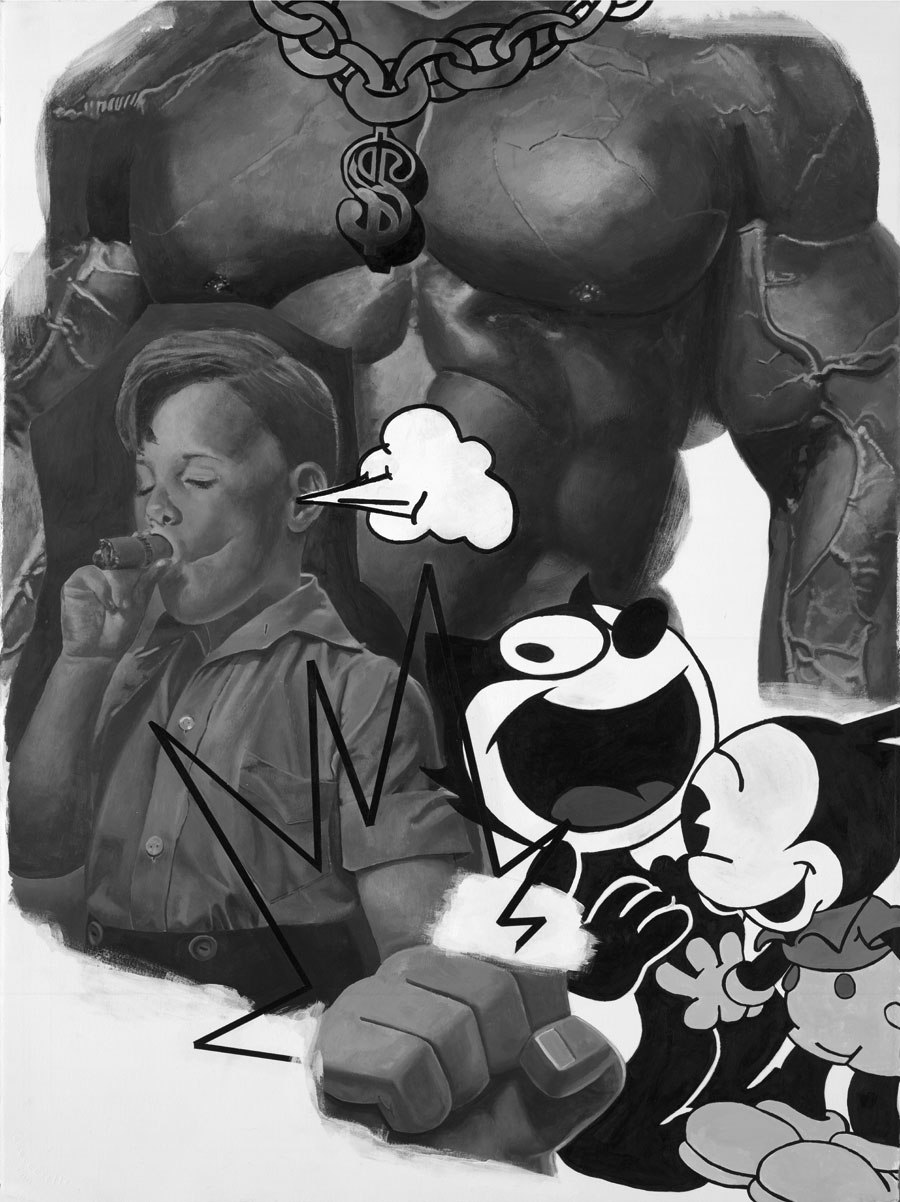

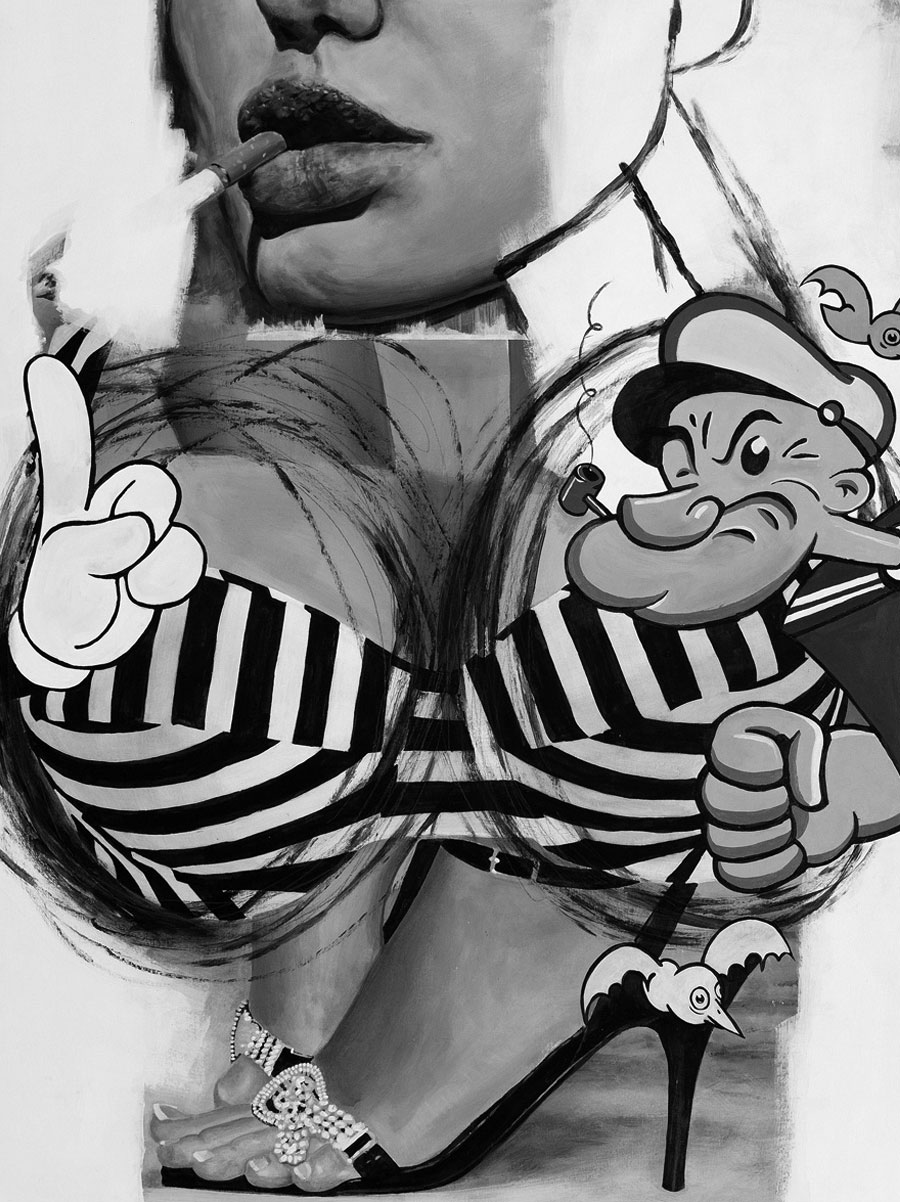

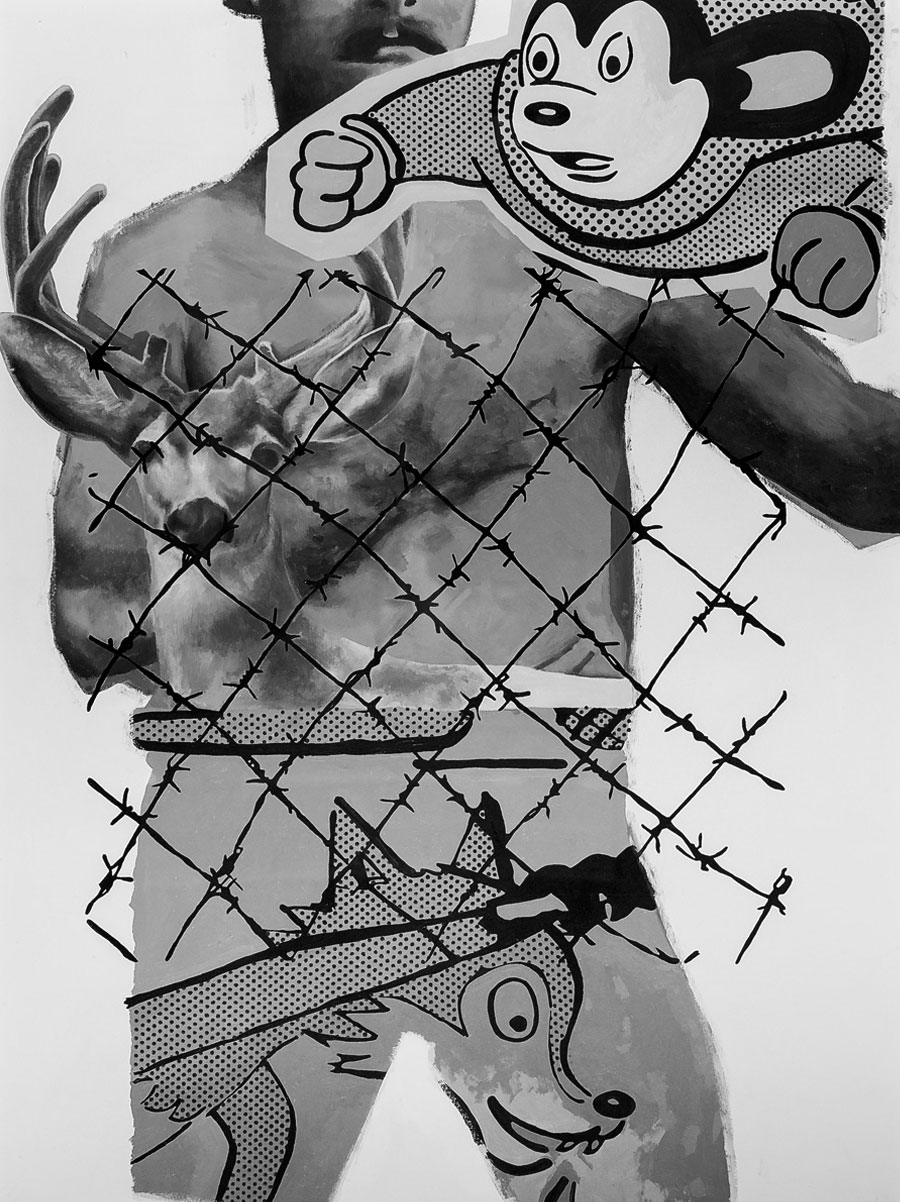

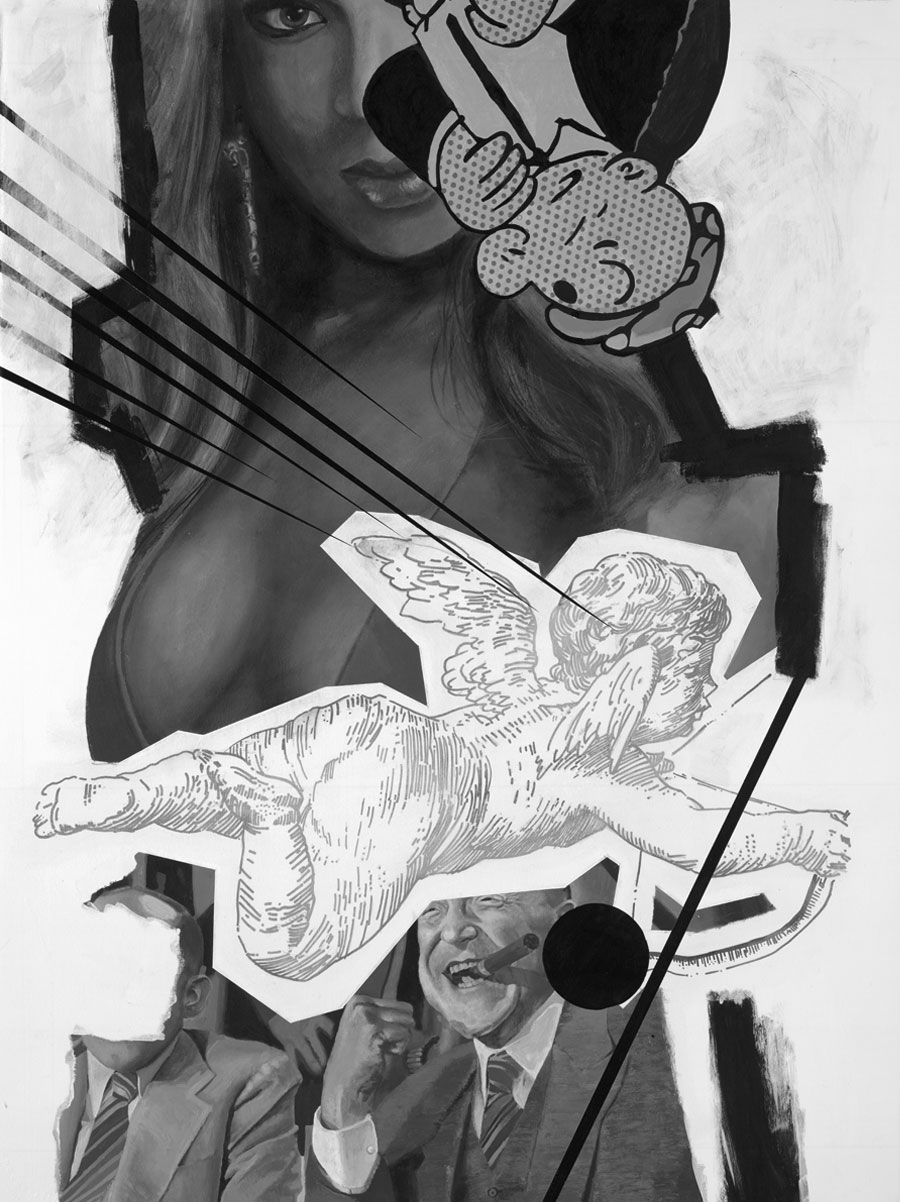

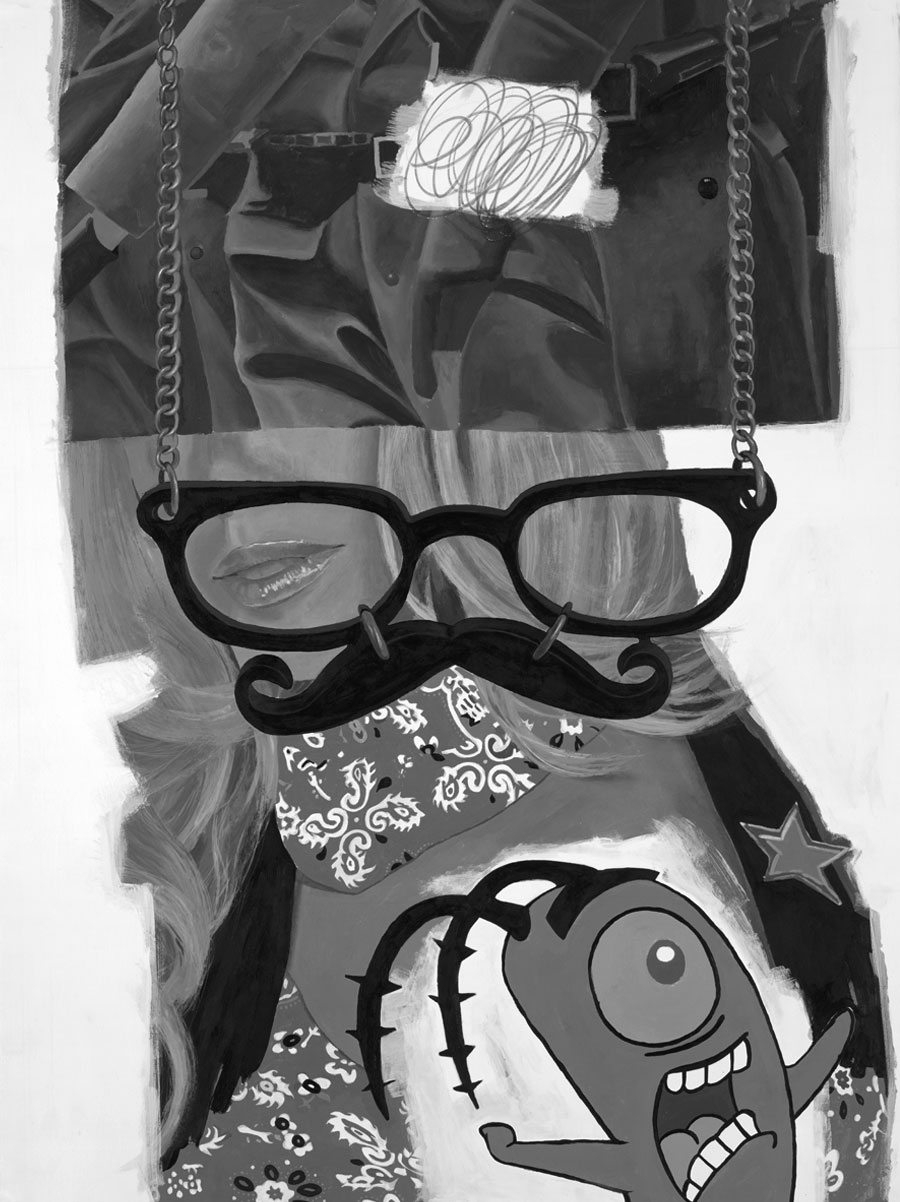

VINCENT SERRITELLA

day job: Effects Technical Director / Pixar

sideshow: Visual Artist / Painting

![]()

artist statement: "Truth or Dare" plays off an age old game that has existed for centuries where a player poses a question and the second player must answer truthfully. If the player chooses "dare", then the first player is given a task. Here the images convey truths and actions where I play the game alone asking the questions and tasking the dares.

In this psychological exploration, I find moments where I've discovered surprises from my subconscious. The black and white aesthetic of this series using acrylic paint on paper reinforces the "truth" or journalistic nature of the imagery. Using humorous, dramatic and cultural references that lay between two-dimensional and three-dimensional planes open the door to my thought process and allow one to look around.

links: https://www.vincentserritella.com, https://www.facebook.com/vsartist

day job: Effects Technical Director / Pixar

sideshow: Visual Artist / Painting

artist statement: "Truth or Dare" plays off an age old game that has existed for centuries where a player poses a question and the second player must answer truthfully. If the player chooses "dare", then the first player is given a task. Here the images convey truths and actions where I play the game alone asking the questions and tasking the dares.

In this psychological exploration, I find moments where I've discovered surprises from my subconscious. The black and white aesthetic of this series using acrylic paint on paper reinforces the "truth" or journalistic nature of the imagery. Using humorous, dramatic and cultural references that lay between two-dimensional and three-dimensional planes open the door to my thought process and allow one to look around.

links: https://www.vincentserritella.com, https://www.facebook.com/vsartist

PETER FREDERIKSEN

day job: Art Buyer / AbelsonTaylor

sideshow: Visual Artist / Painting

artist statement: There is an accepted variety inherent in cartoons that allows for a number of styles of image that, paired with thematic storytelling, is diverse in a way that only some fully realized art is capable of being. Cartoons can be silly, fun, violent, repulsive, and gorgeous, often all in a single image.

I like to employ cartoon imagery when representing the banality of living my life as a 25-year-old semi-professional, glorifying something as simple as a spill on a coffee table with hard outlines and larger-than-life colors and titles, all in a style that owes itself to years of watching Looney Toons with my father. My themes and concepts are rooted in some sense of bachelor domesticity meeting your run-of-the-mill fears of inadequacy and existential concerns, blurred by cartoonish abstractions, thick and clumsy lines accenting forms reminiscent of Sunday mornings in front of the television.

links: https://pefrederiksen.tumblr.com/

DENNIS O’REILLY

day job: Writing Manager / Tether

sideshow: Fiction Writer

artist statement: I’ve always been a writer. Whether stories, songs or copy, I’ve always found my rhythm, my surest footing in sentences and syllables. I was going to explain how story differs from visual arts, but in many ways, done correctly, story is a visual art. The difference—the unique quality that makes a well-told tale so alluring to me—is that a story invites the reader in to construct and color the visual. It’s no longer my imagining, my creation alone. You build the characters, the scenes, the subtle shifts and facial expressions from the raw materials words provide. Your part in the telling is so vital that any attempt to bring the tale into a visual medium negates your contribution. That’s the connection I seek every time I string sentences together; the power to rope you in and, ideally, never let you go.

FROZEN

A STORY

Sometime before three, when the power went out and his alarm clock went dark, Gerard gave up on sleep. Sucking in as deep a breath as his back would allow, he rolled off the edge of the bed, careful not to wake his wife. Even through wool socks the floor was ice. He quickstepped from the bed to the window like a firewalker. The frost, crystalline fossils of ancient ferns etched into the pane, slid off in a brittle sheet, sticking to his sleeve. He licked at it, absentmindedly, like a child. The plows had passed twice in the night, and he had expected the damage to be worse. The bank that hemmed in his driveway was only two, maybe two and a half, feet high, and not nearly as deep as it would have been if he hadn’t gotten out there the previous night.

He dressed slowly, dropping his flannel-lined Carhartts to the floor and working his feet through the legs before he could even think about bending to pull them up. Downstairs he wasted five minutes filling up the Mr. Coffee before he remembered there was no electricity. He put the kettle on the gas stove, and while the water warmed, he took two Tylenols with codeine from the bottle he kept in his pocket and swallowed them dry. Then he lowered himself into the chair at the end of the table. The water boiled away while he waited for the analgesic to soften the stab; by then he couldn’t have gotten up if he’d wanted to. Four days out from his last cortisone shot, he shouldn’t have shoveled. But what choice did he have? If he left it, it would be nine feet high and six deep—not a manageable two by two. Even with his back seizing up, squeezing so hard he saw stars in his periphery, he knew he could handle two feet of slush. It was just a question of when the codeine would kick in.

A little after five, the banister at the top of the stairs creaked. Too early for his son to be up. The newspapers the boy delivered each morning rarely arrived before six, and that was on days without snow. Gerard held his breath as the soft patter crossed the floor above, hoping it was not one of his daughters toddling to the stairs. He had planned to be out of the house before anyone got up. Out on a service call, or just out, if there were no calls. He felt bad pawning the girls off on their brother and leaving the boy, who was only eleven, to take care of his three younger sisters. He told himself he had no choice. He had to work. Their mother, his wife, was sick, in bed most of the time now. “Psychosomatic,” the doctor had said. Which meant something new each day. Some new and mysterious ailment that had no cure. He had done all he could for her, but nothing helped for long. At first he had only leaned on his son when he absolutely had to. But now it was a given, and he had trouble meeting the boy’s eyes most days.

The boy leaned over the rail, peering into the darkness below. He hadn’t noticed that the power was out. He was looking for signs that his father might still be asleep, and his heart leaped at the absence of the rhomboid of lemon yellow light that normally spilled from the kitchen, glinting like frost off the front hall’s worn slate floor.

The boy tiptoed downstairs. He removed his hockey stick, ice skates, gloves, and shin guards from the front hall closet and stuffed the gear into a small duffel bag. Then he slowly, silently opened the front door and put the bag and stick on the porch. As he closed the door, he turned an ear toward the staircase. The only sound: the ticking of the hot water pipes struggling to carry heat through the house.

Gerard knew what his son was up to. Ever since the first good freeze, the boy had begged to be allowed to join the weekend pickup games out on Swain’s Pond, but Gerard had refused. Now, thinking his father was still asleep, the boy was hoping to slip out, deliver his newspapers, and then sneak off to the pond. If it hadn’t been for the twisting fire in his lower back, Gerard would have confronted him right then. But he could hardly draw a breath below his collarbone, so he sat there in the shadows, watching his son steal about like a thief.

The boy almost turned the kitchen light on—a reflex—but caught himself. He shuffled toward the ghostly outline of the refrigerator and pulled the door. He became aware of the hiss of the teakettle, a fat cast-iron hen nested in the blue flame of the burner, but was only beginning to realize the implications of what he saw when his father spoke in a low voice. “Shut that goddamn door.”

The boy jumped. Gerard felt bad, yelling at him first thing. But he couldn’t just sit by while the kid stared into the dark of the ancient Amana, letting the cold out. Goddamn kid didn’t think sometimes. Most of the time, actually. “Close it.”

Associating the tone of his father’s voice with an imminent smack upside the head, the boy pushed the door closed so quietly it didn’t make a sound. “I was just—”

“The power’s out,” Gerard said. Not as an apology. He didn’t like excuses; the kid was full of excuses.

After a long, cautious minute, the boy took a slice of Wonder bread from the plastic bag on the counter and resealed it with the twist tie. He wanted cereal, but he knew there wasn’t any milk. There were no clean butter knives, so he scooped a spoonful of Skippy from the jar on the counter and wiped it across the bread, tearing up big clumps that made him want to throw it away. He folded and ate the sandwich, and then filled a glass from the tap, nervous even though he knew cold water ran regardless of electricity, and their water heater was gas, anyway.

Gerard was about to ask the boy why he’d put his skates out on the porch when the phone rang, startling them both. Through clenched teeth, Gerard said, “Get it. Before it wakes the whole damn house up.”

The boy grabbed the receiver and brought it to his father, pausing once to untangle the long, curly cord. While his father whispered into the phone, he drained the glass and placed it gently on top of the dish towel that lay next to the sink.

When he got off the call, Gerard handed the receiver back to his son and, in a cold, even voice, said, “I need you to run by Mrs. Herzog’s with me.”

The boy nodded, but there was no mistaking the look of resentment on his face.

“It won’t take long,” Gerard said. “We can put your papers on the sled. I’ll pull, and you can run ’em up.” When the boy didn’t respond, he added, “Mrs. Herzog’s power’s out.”

“Isn’t everyone’s power out?” the boy asked, his voice tinged with sullen anger. From where he stood, he couldn’t see the hint of a smile crease his father’s face.

“Yeah,” Gerard said. “But not everyone’s ninety-three.”

Mrs. Herzog lived three blocks down, on Old Brook Circle, in a small one-story house. She had lived alone for thirty-one years. Her two oldest children were dead and her surviving son, Davey, who suffered from emphysema, lived near Reno. She had three grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and four great-great-grandchildren, but no one in the state. Though lucid and able-bodied, she rarely left her house. A natural talker, she often caught herself entrapping people in lengthy conversations, thinking of new topics while they were still answering her previous questions, playing up her neediness and helplessness when she thought it might work.

It worked on Gerard. Despite the fact that he could hardly afford to give anyone freebies, he showed up whenever she called—at least twice a month—and never charged her, even when she actually needed work done. He told her the paperwork was more trouble than the job was worth, even though he figured she probably cost him a thousand bucks a year in lost time. This time she refused to believe everyone’s power was out. She swore she could see lights on in the house across the street. He was glad she’d called. It got him out of the house. (He wasn’t expecting any other calls, as electricians are hardly in demand when there’s no electricity.)

He looked at his son. Moping, feeling sorry for himself. He felt that familiar sense of guilt. The things he swore he’d never do when he had kids. But the boy was the one who’d told Mrs. Herzog, one of his paper route customers, about his father the electrician in the first place. Besides, Gerard wasn’t asking much.

“We won’t be there long,” he said. He drew in a lungful of shattered glass as the deep, wet snow beneath the red plastic sled full of papers gave way to his pull. “We’ll just check the fuses. Convince her the power’s really out. Make sure the pilot on the stove’s lit. Then you’re free.” He watched his son’s eyes for a sign of guilt but saw none.

The boy took a Globe from the pile and trudged up a walk. He opened the screen door and let the thick paper hang in midair for a split second as he deftly snapped the door shut.

“You got plans or something?” Gerard asked, ready to catch him in a lie. But the boy was ready. He volunteered that he was going to a friend’s house and, if the roads were clear enough, the friend’s mother was going to drive them to Flynn Rink for open skate. “And if the roads aren’t clear enough?” Gerard said.

“We’ll prob’ly just build a snow fort or play on his Atari or something.”

Atari. Last year, his wife had suggested the boy ask Santa for it, and the kid was quietly crushed when the last present was opened.

Gerard handed his son the snow shovel he carried on his shoulder and told him to clear Mrs. Herzog’s front walk and stairs. He trudged up the unused driveway to the back door and knocked hard.

“Who is it?” she hollered, even though she had been standing by the window, veiled by lace curtains. She had watched him pull the sled, his face twisted in paroxysms of what she knew to be pain—not rage, as it might have appeared to someone who didn’t know him as well. It made her happy to see Gerard and his son together. In the past, whenever she’d complimented him on his son’s wonderful manners, he’d always shrugged it off, as if she didn’t know the truth of it. As she made her way to the kitchen, she heard the scrape of the boy’s shovel, muffled by the walls, like a coal shovel scooping the last lumps of grimy black from the basement floor into the furnace. It gave her a warm feeling.

Gerard pushed the back door open and stuck his head into the kitchen, careful to keep his snowy boots outside.

“I’m coming,” she called. “Hold your horses.” Mrs. Herzog almost smiled when she saw him, but lowered her brow and cranked, “Don’t track mess all over my kitchen floor. At least kick those clodhoppers off if you have to come in.” Seeing him remove his boots each time he entered her home filled her with a joy she couldn’t explain.

This was their routine. A pantomime, repeated, with subtle variations, throughout the year. Knowing the script by heart, he hadn’t tied his boots and, when she complained, he pried them off with a grunt and stepped into the kitchen in his gray wool socks.

He scanned the old dusty kitchen. Exactly as it always was. Right down to the centerpiece on the table: a ceramic napkin holder shaped like a Thanksgiving turkey, with a slot in its tail feathers for napkins, a fat ear-of-corn saltshaker, and a gourd-shaped pepper mill. It had been there the first time he’d come to her house, in late April, more than three years before. Whenever he saw it, he couldn’t help but picture the room as it might have been: bright and loud, full of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Everyone crammed in, smiling and laughing. A shy little boy hiding behind his mother’s legs to avoid the scary old woman. And that stupid turkey, right there in the middle of it all. Now it was faded on the side that caught the afternoon light through the kitchen window. The crown was chipped, and the tops of the shakers were covered in a thick froth of greasy dust. She just left it there, letting it waste away.

The pilot light on the gas stove burned a steady blue. Mrs. Herzog refused to stoop to see it. “I’ll take your word for it,” she said. She made small talk until the boy, standing at the bottom of the back stairs, called out, “Dad?”

Gerard went to the back door. “What the hell’re you yellin’ about? Get in here.”

The boy too left his boots on the stoop, but lingered in the entryway. The house reeked of mothballs. Mrs. Herzog had an unpleasant smell about her most of the time too. Probably because she was always wearing the same stained shawl over her housedress, even on the hottest, most humid days of summer. Old vulture, he thought, staring at her hunched shoulders and hooked nose. Not a real vulture, but a cartoon vulture. Like one from The Jungle Book. A character he shouldn’t have been afraid of, though he was. Afraid to speak to her, afraid to be in the same room as her. Despite her smile and her kind eyes and the way she acted as though every word out of his mouth was the greatest thing she’d ever heard, he was pretty sure she was the one who told his father what he’d said about his mother. It wasn’t bad, what he said. She’d asked about his family, and he’d told her the truth. But then his father came back from a call at her house and threw him against the wall in the hall. He screamed in his face. “If you ever—ever—bad-mouth your mother to anyone ever again, I’ll make it so you never say another goddamn word as long as you live. Got me?”

Since that day, just to be safe, he hadn’t said anything about his mother to anyone. Even people who knew her and asked how she was. He’d also gone out of his way to avoid Mrs. Herzog, sometimes even paying her paper bill—$2.35 a week—out of his own pocket rather than risk letting something slip when she kept him standing there in her kitchen, asking all kinds of questions as she counted out nickels, dimes, and pennies. Now here he was, in the kitchen with both of them. His father a powder keg and Mrs. Herzog a book of matches.

The old woman stood by the stove, watching the boy. “You did too good a job,” she said. “Now my walk’s gonna be a sheet of ice when it freezes tonight. I’ll prob’ly slip and break my neck.” She smiled.

The boy didn’t so much as breathe.

From the pockets of his work coat, Gerard removed a small flashlight and a voltage tester, a red cylinder with two probes, one black and one red, dangling from wires off one end. He told the boy to stand in the basement doorway and then pointed to the ceiling fixture.

“Holler down if that comes on.” He wanted to wink, to let the boy know that they were in this together and it would be over soon, but he didn’t.

As Gerard made his way down the steep, dark staircase, he felt as if his spine were on a spool, being wound tighter and tighter, his legs reeling up, shorter with each step, and so he had to reach farther down to find his footing. Dutifully, he checked the line coming into the service board from the street. Then, for no logical reason he could think of, he unscrewed the main fuse, blew on the end of it, and screwed it back in. When it was snug, but not so tight that the threads might strip, he turned and yelled, “Anything?”

“No,” the boy yelled back, with just a hint of sarcasm.

“It’s not. A fuse.” Gerard was out of breath from the climb back upstairs. “Must be. The whole grid.” He swept a hand, encompassing the whole neighborhood. “Should be back up soon.”

They both knew that wasn’t necessarily true. Their neighborhood was usually the last to get its power restored.

“Well, whom shall I call about this?” she asked.

Gesturing to the small Formica-topped table and the two straight-backed chairs, he said, “You stay out here. Turn the oven on and open the door for a little while, just till you’re warm. Want me to fire it up for you?”

He knew the answer but wanted her to be the one to mention the portable.

“Don’t you touch that oven,” she said, firmly. “I’m not gonna freeze to death out here. I’m staying in my living room, where I can keep an eye on the street. I have the space heater my Davey bought me.”

Gerard shook his head. Soon as he’d stepped into the house he’d smelled the heater, like someone holding a Zippo to human hair, but he’d waited to bring it up. He vaguely recalled arguing with her over the safety of propane heaters once; obviously, he hadn’t won the argument. Her idiot son had talked her into converting the whole house to electric baseboard heat back in the early seventies, convinced oil heat was the cause of his lung problems. Then, he’d taken his idiocy a step further, giving his elderly mother a propane heater the first time she called to complain.

Frowning, Gerard marched into the living room, a clutter of threadbare furniture, lace doilies, and crocheted afghans. Kindling. He touched the side of the heater nearest the couch, and then shut it off. The switch alone would have burned the tip of his finger were his hands not so calloused, the skin so thick. “This has to cool down,” he said. He called his son from the kitchen—the boy was still standing by the door—and told him to take the heater out to the garage before it burned the whole house down.

“Have you lost your marbles?” the old woman said, not moving to stop them. “How’m I gonna stay warm if my heater’s in the garage?”

She meant it the way she meant everything she said to him, part of their ongoing repartee, but this time Gerard didn’t smile back. “How?” he snapped. “Sit in the kitchen, with the doors closed and the oven on and some blankets on your lap. That’s how.”

Her smile cracked, but she didn’t let it fall apart completely. She knew he didn’t mean to snap at her like that.

Gerard looked out the large picture window that opened onto the blanketed street. “These heaters . . .” he said. He shook his head. When she offered no further protest, he nodded to his son. The boy lifted it cautiously, holding it away from his body. Gerard said, “Don’t tip it. Jesus. Pay attention to what you’re doing. Hold it by the handle.”

He followed the kid into the kitchen. “When you get outside,” he whispered, “pull this plug”—he tapped the fuel cap on the top of the heater—“and dump the propane in the snow on the side of the garage.”

The boy looked up at him, fear in his eyes, not understanding.

“Just do it,” his father hissed. And then, in full voice, added, “Put it right in the middle of the garage, not near anything.”

The boy did as he was told, accidentally spilling a little propane on his boot. He stood the heating unit in the middle of the empty garage—Davey had sold her ’69 Pontiac Bonneville on his last trip back east—then stood back staring at it and wondering what would happen when Mrs. Herzog got too cold. Would she come out for it? Could she make it all the way to the garage? What would she do when she realized it was out of gas? And what if the electricity didn’t come back on? What if she froze?

He didn’t go back into the house. He stood at the foot of the stairs, knifing his boot into a snowbank, working it around, hoping the snow would leach some of the propane off. His father was standing by the back door, trying to ease himself out.

“You’ll be warmer in here,” Gerard said. He’d already lugged her armchair, an ancient beast of heavy wood covered in rough fabric, in from the living room, along with her needlework basket and three blankets. “If it gets too cold, just turn the oven on for a few minutes. You’ll be fine.” She looked dubious. “If the power doesn’t come back on, I’ll stop by later to check on you.”

They both knew he would end up stopping by whether the power was back on or not. Still, she griped reflexively. “Pshaw! Leave me without my heater! How am I supposed to get it in from the garage? And what if the pilot does go out? My house’ll blow up! I want my heater back. You don’t know anything bad’ll happen.”

As the load of papers diminished, the sled moved more easily and Gerard was able to take deeper, more satisfying breaths. He rested while the boy ran two papers up to a duplex. When his son came back, he had wind enough to tell him he’d drive him to his friend’s house.

“That’s okay,” the boy said quickly, without looking up.

The way he evaded his gaze made Gerard want to call him on his lie. Punish him for it. He bit the inside of his cheek until his anger passed, and then said, “I don’t mind.” He watched his son struggle to pick up the last paper with his gloved hands. “I don’t want you to miss your ride to the rink.”

After he dropped his son at the foot of his friend’s driveway, Gerard drove home. The girls were downstairs now. The two little ones on the rug in front of the TV. The eldest, now almost seven, turned the dials, and then smacked the top of the set. He yelled at her, and then all three started to whimper. He herded them into the kitchen and poured out bowls of Rice Krispies for the little ones. There was no more milk, so he helped the big girl toast two slices of Wonder bread under the broiler. When they’d eaten, he marched them into the mudroom and bundled them into snowsuits, boots, hats, and mittens, which he clipped to their sleeves with difficulty. They waddled off to the back porch. He returned to his place at the table. He could hear the steady trickle of melt in the drainpipe, and every once in a while, a thick frosting of snow sloughed off the roof and landed with a dull thoof.

A little after noon, his wife came downstairs. She stood staring at the empty Mr. Coffee until he said, “The power’s out.”

“You didn’t dig out the Mirro?” she said, referring to the old stove-top percolator. “You know my migraine’ll get worse if I don’t have coffee soon as I get up.” He didn’t argue or apologize. Without thinking, he watched her pour boiling water into a mug. When she realized there was no milk for her tea, she began to cry. She stood there, as if to give him a chance to explain or to offer some solution, but he didn’t even look at her. Finally, as though she didn’t know what else to do, she climbed back upstairs, back into their bedroom, back into bed.

Sometime later, Gerard chewed two more Tylenols with codeine. When the pain softened to a dull ache, he called his daughters in and stripped them back down to their pj’s, his frozen hands fumbling the tiny zippers and buttons. He dropped a square of butter into the big cast-iron frying pan and watched it skate over the surface, thinner and thinner; he almost forgot to add the bread and Velveeta. As an afterthought, he heated a can of Campbell’s Chicken Noodle. Soon as they were done eating, he forced them back into their wet snow clothes and back outside. This time, he watched from the window for a few minutes. They made snow angels until the littlest one trod on them. Before he sat down again, he dissolved four ibuprofen tablets under his tongue, savoring the bitterness. The kitchen was dark. His eyes sought the clock on the wall, but the hands were lost in shadows. He knew he should bring the girls inside before it got too cold.

When the phone rang, he felt it more than heard it. As if the bells were soldered to the top of his spine, rattling his teeth loose. He put his hands to his ears and pressed hard against his skull until his eyes popped like flashcubes, but this didn’t lessen the pain. He tried counting the rings, inhaling on the third, exhaling on the fifth. But by the seventh ring, the interval between rings had tightened, and he couldn’t keep up. With the ninth, the tone changed, became more insistent, more urgent, and the possibilities of who could be on the other end diminished greatly. Especially on a Sunday, during a power outage.

“Can’t you hear the goddamn phone?” his wife hollered down from the top of the stairs. Her voice a ball-peen hammer tapping his molars into his gums, into his jawbone.

He did, of course. But he didn’t want to get it. He didn’t want to be the one to have to deal with it. He wanted to sit where he was forever. Never move. Let fate do what it had to do. Let God do what he had to do, but leave him out of it.

Eleven was devoid of tone, sharp and metallic. He could taste it, like a penny on his tongue.

He tried to picture the old woman, sitting at her kitchen table, absently wiping a stripe into the dust on the tail of the turkey, but he couldn’t hold that image. His mind darted back to when he’d dropped his son off, watching for a moment as the boy trudged up the pristine walk. Gerard knew—he didn’t think, he knew—that as soon as he was out of sight, his son would turn and head for Swain’s Pond, to the ice. He had let him go. Driven him halfway there, for Christ’s sake. He had taken Mrs. Herzog’s heater away, but he let his son go. All because he wanted—what? Did he think he could make up for everything? For life? For the fact that life wasn’t fair? He knew better. He wasn’t the boy’s friend; he was his father. It was his job to keep him safe. His job to know. Whatever had happened was his fault. His responsibility. Because he knew how life worked. He knew it just kept coming at you until you couldn’t take it anymore. Until you sat down and didn’t even try to get up again.

Gerard thought of his son. “Please,” he whispered. And then he let his breath out in a slow hiss, leaned forward, and pressed the palms of his hands against the tabletop. His lower body was dead weight, pulling him down, pulling him under. The pain started at the base of his skull and shot down his spine, arcing across his shoulders. A rush of blood roared in his ears. He pushed with all his strength against the cold surface and forced himself up, gasping for air.

FROZEN was originally published in Narrative Magazine.

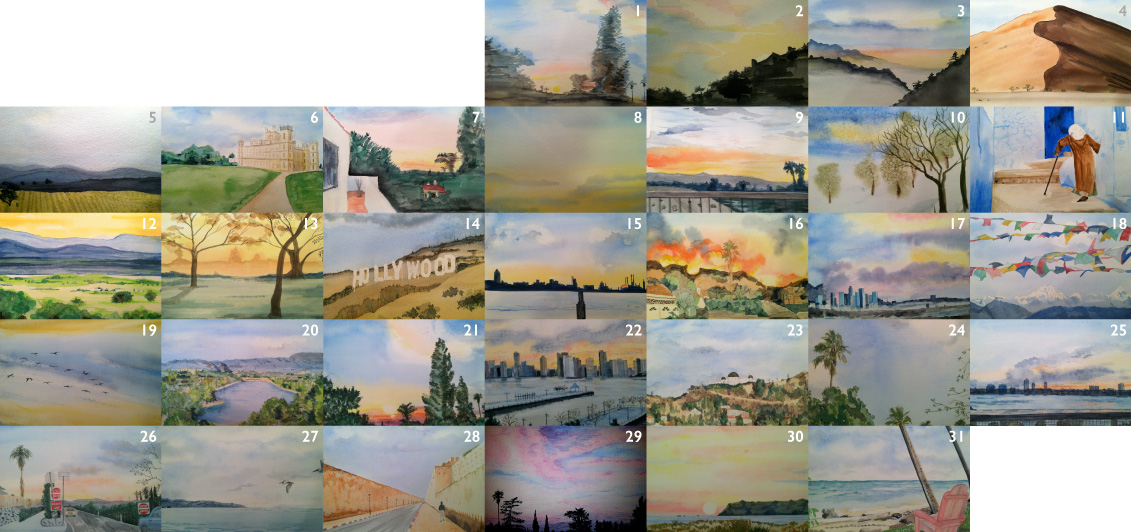

SANAE ROBINSON

day Job: Freelance ACD/CD/Art Director

sideshow: painter/yoga instructor/jewelry designer/urban farmer/knitter

![]()

artist statement: I had just moved back to LA after working in NYC for the past 12+ years. The holidays were over, I was gearing up for the big job search but feeling a bit unsettled and uninspired. I really needed a creative kick start so I decided to embark on an annual challenge to do a fun thing every day for the month of January. I wanted it to be creative and truly a challenge for me, not something I already knew I could do. For practical purposes, it also needed to be something that I could do in an hour or so and be portable. After a trip to my local art store, I found myself with a set of $5 watercolor paints, some brushes and a cheap pad of paper. With these supplies I set upon my challenge: teaching myself how to paint with watercolors by doing one painting a day. And FUN-A-DAY PAINTINGS began!

Day 1 was a bit of an embarrassment to me, a sunset as seen from my backyard deck, done with a tentative hand and sloppy brush strokes. I started google-ing artists, watching how-to videos on YouTube, trying to gather as much knowledge as quickly as I could. I soldiered on. It helped to have my friends in social media-land cheering me on, leaving comments and liking my postings. As the days clicked by I grew more confident. But it’s hard to do something every single day, whether you’re “feeling into it” or not. Some days I’d be so busy I'd have to squeeze it in at the end of the day. Other days I wished I could start over. But I realized that mixed results were just part of the process -- you take a few steps backwards while you’re moving forward.

At a point mid-month, I decided to revisit Day 1 to see how I’d paint it on day 21. In Day 21 I could see my growth and it surprised me. Could I really have learned to paint with watercolors by the sheer diligence of a daily practice?

Now that my 31 days are over I have a great sense of accomplishment in January's body of work. I’ve learned so much, perhaps most importantly to not listen to that inner voice that tells me I can’t do something, but instead listen to the one that says give it a try!

day Job: Freelance ACD/CD/Art Director

sideshow: painter/yoga instructor/jewelry designer/urban farmer/knitter

artist statement: I had just moved back to LA after working in NYC for the past 12+ years. The holidays were over, I was gearing up for the big job search but feeling a bit unsettled and uninspired. I really needed a creative kick start so I decided to embark on an annual challenge to do a fun thing every day for the month of January. I wanted it to be creative and truly a challenge for me, not something I already knew I could do. For practical purposes, it also needed to be something that I could do in an hour or so and be portable. After a trip to my local art store, I found myself with a set of $5 watercolor paints, some brushes and a cheap pad of paper. With these supplies I set upon my challenge: teaching myself how to paint with watercolors by doing one painting a day. And FUN-A-DAY PAINTINGS began!

Day 1 was a bit of an embarrassment to me, a sunset as seen from my backyard deck, done with a tentative hand and sloppy brush strokes. I started google-ing artists, watching how-to videos on YouTube, trying to gather as much knowledge as quickly as I could. I soldiered on. It helped to have my friends in social media-land cheering me on, leaving comments and liking my postings. As the days clicked by I grew more confident. But it’s hard to do something every single day, whether you’re “feeling into it” or not. Some days I’d be so busy I'd have to squeeze it in at the end of the day. Other days I wished I could start over. But I realized that mixed results were just part of the process -- you take a few steps backwards while you’re moving forward.

At a point mid-month, I decided to revisit Day 1 to see how I’d paint it on day 21. In Day 21 I could see my growth and it surprised me. Could I really have learned to paint with watercolors by the sheer diligence of a daily practice?

Now that my 31 days are over I have a great sense of accomplishment in January's body of work. I’ve learned so much, perhaps most importantly to not listen to that inner voice that tells me I can’t do something, but instead listen to the one that says give it a try!

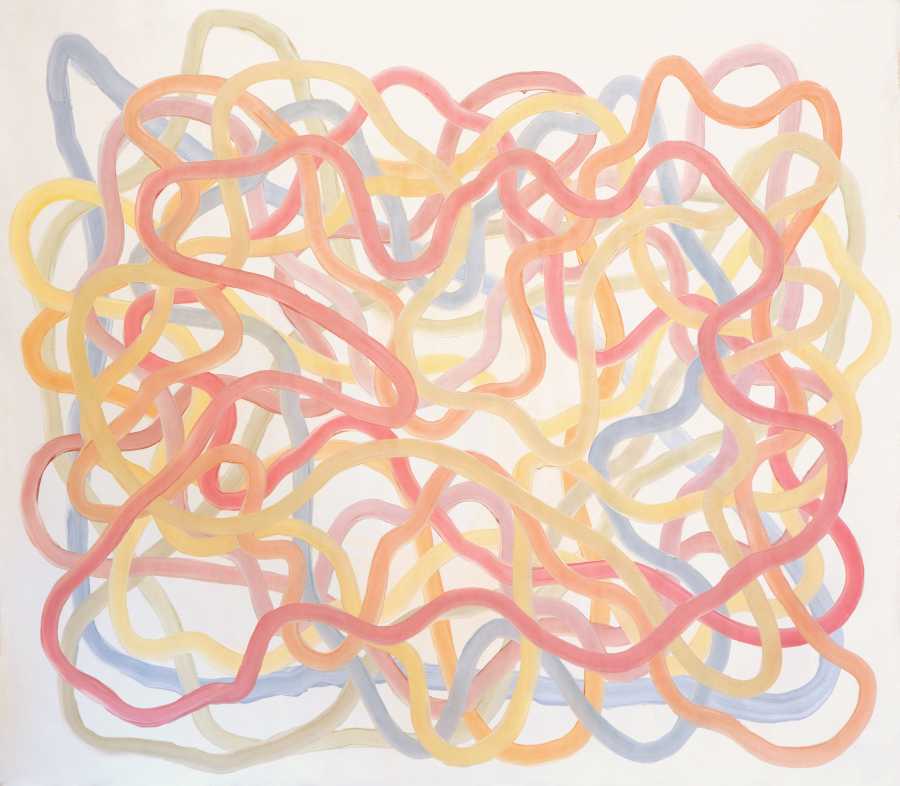

ROBERT STONE

day job: Graphic Designer/Creative Director; Currently Co-Founder/Chief Creative Officer at a new financial services start-up

sideshow: Visual Arts / Mixed Media

artist statement: After admiring and collecting abstract art for many years, I decided a few years ago that it was time to create some of my own. I've never been compelled to paint situations from life, to interpret humanity or nature, or make pictures of objects or things. What excites me is trying to create an emotional and visceral reaction to the subtle interaction of basic visual elements: line, shape, color (or lack of color), mass, scale, texture, and light.

I often feel that what drives me is a never-ending search for a perfect composition. But as it turn out, my pieces actually do tell unintended stories for different viewers. Some people see human figures, others see landscapes and still lifes, while others see geological formations. I hear comments about the contrast of complexity and simplicity. That the paintings are dark and mysterious while also being open and inviting. That they appear random and violent, but also logical and peaceful. Creating those juxtapositions is what I find most intriguing and gratifying.